Science fiction and technology writer

Popular blog posts

Recent forum posts

Discussion Forum

Discussion forumMy article on the history of public messaging is up on Ars Technica!

Post #: 304

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2024-04-29 15:02:37.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Articles

This article was deeply personal to me, because my life overlapped with so much of it.

It starts out with the earliest networked computers (PLATO, and the Arpanet) and goes through BBSes, Usenet, web-based forums, and social media. It's a wild ride.

Check it out!

https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2024/04/first-post-a-history-of-online-public-messaging

Views: 3696

Micro History Episode 0 is up!

Post #: 303

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2024-04-23 17:38:49.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags:

It's an exciting beginning for me, the culmination of a dream I've had for a long time, to chronicle the entire history of personal computing.

Enjoy and don't forget to like the video and subscribe to the channel!

Views: 10286

Jeremyreimer.com is live on a new server!

Post #: 301

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2024-02-19 21:43:01.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags:

If this works, you should be seeing a new blog post!

I migrated all my websites from AWS to Linode. It's a lot cheaper, and I really like the simplicity of Linode server management.

Onwards to new things!![]()

EDIT: Just checking image uploading! Still works!

Views: 11952

How is Facebook's Metaverse doing? Worse than buggy, it's lonely, boring, and bleak

Post #: 300

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2023-03-21 20:15:20.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: gaming metaverse

In a previous article I posted my thoughts on Facebook's sad attempt at a Metaverse, and how it was already failing shortly after launch.

Some time has passed, and I have an update, courtesy of journalist Paul Murray: https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/mark-zuckerberg-metaverse-meta-horizon-worlds.html

"After a certain number of hours in Zuckerberg’s personal universe, you find yourself asking questions like “Does he think this is good?” Looking through my notes, I keep coming across words like diminished, depleted, wan, bleak. The beta-ness of it all is mystifying. If I were Zuckerberg and I’d spent $36 billion building a metaverse, I’d make sure when I launched it there was something to do. Why would he go to all the trouble of building a virtual world, then leave it to the users to make their own fun, as if they were at a holiday camp in the ’80s?"

...

"I can’t stress how unlike a party house the Party House is. It’s not just the amateurish, low-tech design; it’s not just the sparse attendance and desultory interactions. It’s the total absence of mood. It reminds me of when I’d try to get together with friends over Zoom during lockdown — everyone’s face appearing in a box in the grid like contestants in some bleak, prizeless game show, the total absence of physicality making us feel more distant from one another than ever."

Bleak, deserted, lonely. I'm glad Paul spent some time in Facebook's Metaverse so that I don't have to.

Views: 12806

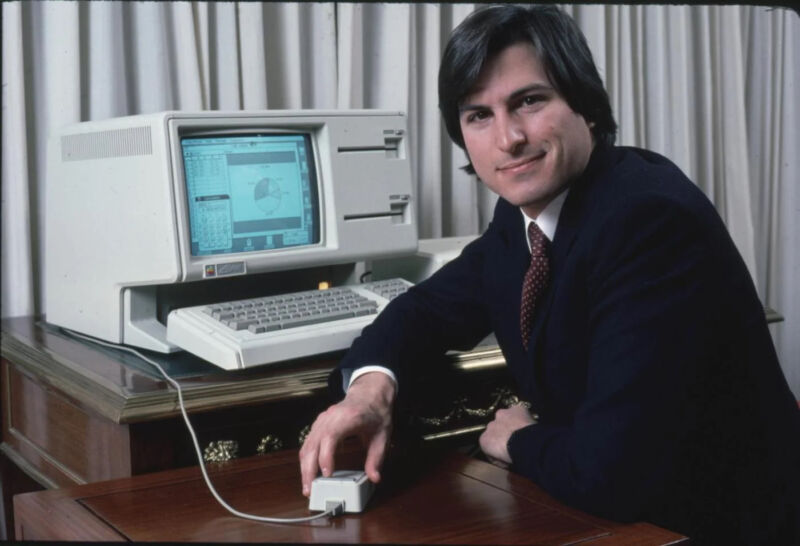

Revisiting Apple's failed Lisa computer, 40 years on

Post #: 299

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2023-01-19 21:27:36.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: articles

A second article in less than a week! This one's about the revolutionary yet forgotten computer from Apple, the Lisa, which was announced today, forty years ago.

https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2023/01/revisiting-apples-ill-fated-lisa-computer-40-years-on

With this second article, I had the strange feeling of being bumped off the front page of Ars Technica by... myself. My editor called it "Reimer week". It's been fun!

Views: 4213

The History of the ARM chip: Part 3

Post #: 298

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2023-03-21 16:40:22.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: articles

The third and final article in my History of the ARM chip series is now live on Ars Technica!

Read it here: https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2023/01/a-history-of-arm-part-3-coming-full-circle/

This article focuses on how ARM changed the world, from the iPhone to the Game Boy Advance to smartphones and Apple's new computers based on the M1 chips. It ends with a look at how ARM managed to succeed when so many other technology companies failed.

I hope you enjoy it! Please share it with your friends!

Views: 11555

The History of the ARM Chip: Part 2

Post #: 297

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2022-11-22 02:16:19.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: articles

This morning I was happy to find that Part 2 of my History of ARM article is now live on Ars Technica. You can read it here:

https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2022/11/a-history-of-arm-part-2-everything-starts-to-come-together

The first part was mostly a technical story of talented engineers who created something amazing. The second part is the story of how the ARM company was able to bring this technology to the world. It's a reminder that it takes both technical prowess and a focused business approach in order to succeed.

Part Three is coming next month!

Views: 9042

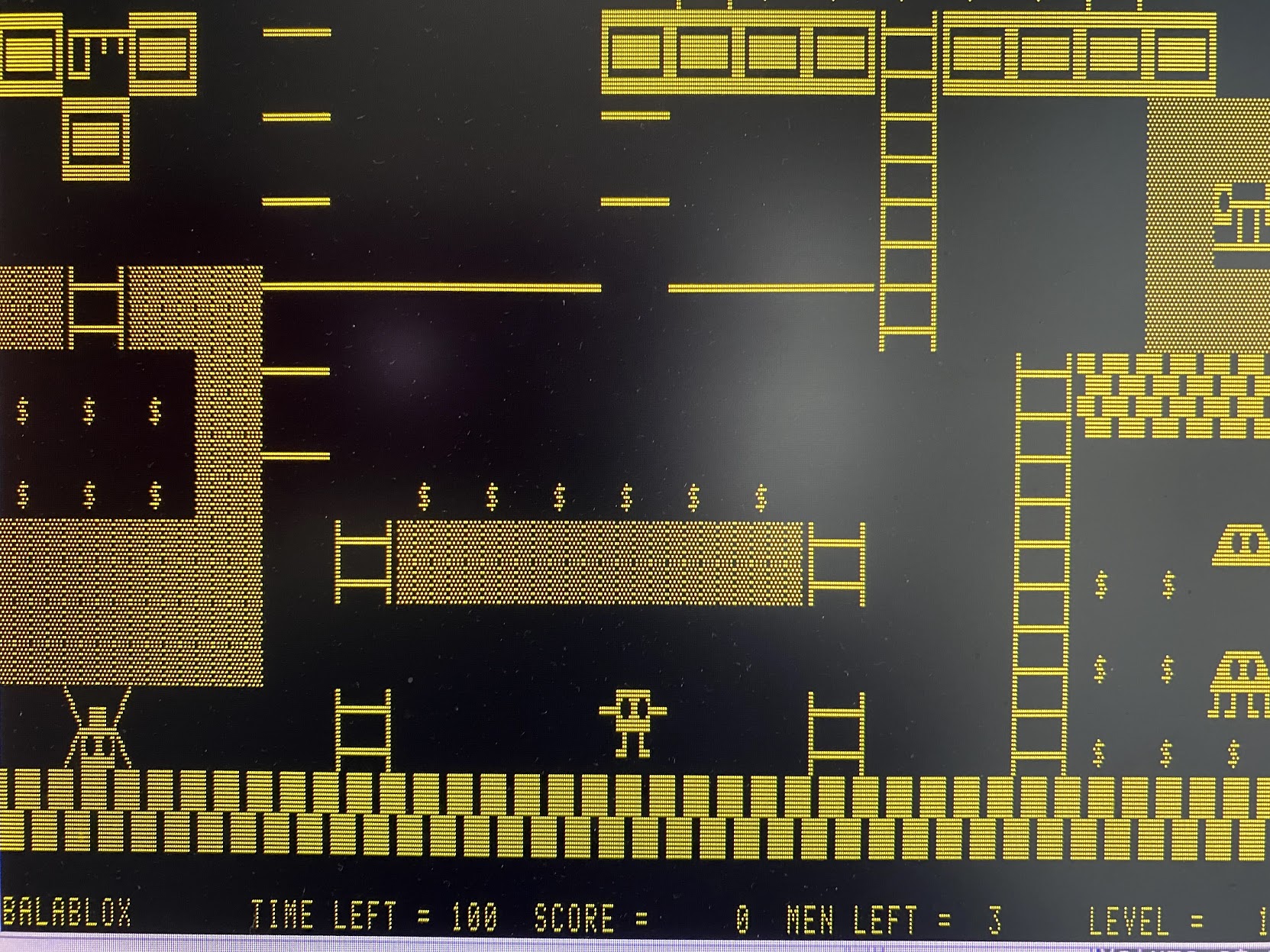

Reimagining the most obscure video game ever made - Part 1

Post #: 296

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2022-10-28 05:23:08.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags:

The original game, running on my Heathkit H-89

A while back, I wrote about the most obscure video game ever made, called Balablox, which I wrote when I was 15 years old in 1987. At the end of the article, I teased the possibility of a modern rewrite.

I’ve been working on that project, on and off, for about half a year now. My goal is to get it finished this year, for the 35th anniversary of the game. It’s been a ton of fun. To celebrate, I decided to write a series of articles about how I made the game, and what I’ve learned through the experience.

Everyone agrees that developing games is hard, but why is that? Don’t we have much better tools and languages now than we did back then? How hard could it be to make a simple game in 2022? Read on to find out!

Choosing an engine

These days, the first thing you do when you decide to make a game is to pick an engine. Game engines didn’t exist 35 years ago—every game was made from scratch. Today, the most popular game engines are Unity and Unreal. But these engines are ridiculously powerful, and take years to master. They’re designed so you can make any sort of game, including modern AAA titles with advanced 3D graphics and multiplayer support. They’re a bit overkill for what I wanted to make—a simple single-player game with very simple 2D graphics.

I ended up choosing GameMaker Studio 2. I made this decision after watching a series of YouTube videos where Yahtzee Croshaw (of Zero Punctuation fame) created 12 games in 12 months. A month to write a simple game? That seemed achievable.

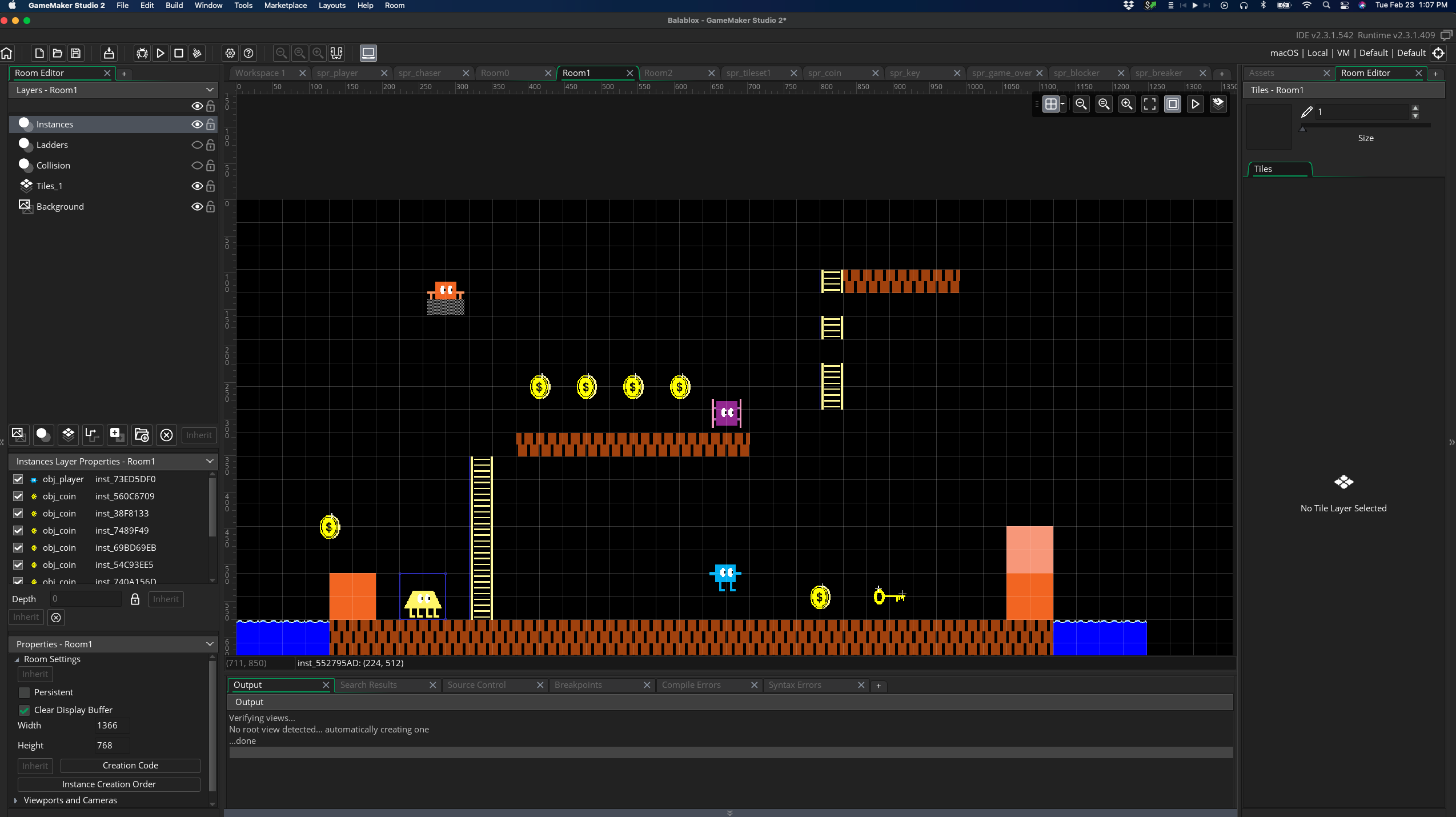

My first steps working in GameMaker Studio 2

In the end, no matter which engine you choose, you should commit to it. You can end up spending months just playing around with different engines, or reading endless forum discussions about which one is better. All this is time that you aren’t making a game. And whatever you do, don’t switch engines mid-stream!

First things first

GameMaker Studio, like any of the game engines, takes a while to get used to. Because it’s based around 2D images, or “sprites”, it has a sprite editor built in. So the first thing to do is create a sprite for the player character.

Balablox was built on my ancient Heathkit H-89, which only supported character-based graphics. In any case, the characters were supposed to be blocky, like the cartoon that inspired it. So I stuck with a simple rectangle to start, and attached stick arms and legs. But using the power of pixels, I added large expressive eyes. That felt like a good compromise between the old and the new.

Editing the player sprite

How big should the sprite be? On my laptop’s screen, 32 by 32 pixels looked about right, and it’s a nice computer-y number to use. Done! Now I could make an “object” that used this sprite and place it on the screen grid for the first level, or “Room”.

But an empty room isn’t any fun to play in. GameMaker lets you design levels the same way people did in the original Nintendo days—as grids of tiles. I wanted a bit more granularity for the room tiles, so I made them 16 by 16. This seemingly innocent choice would cause me a lot of headaches later!

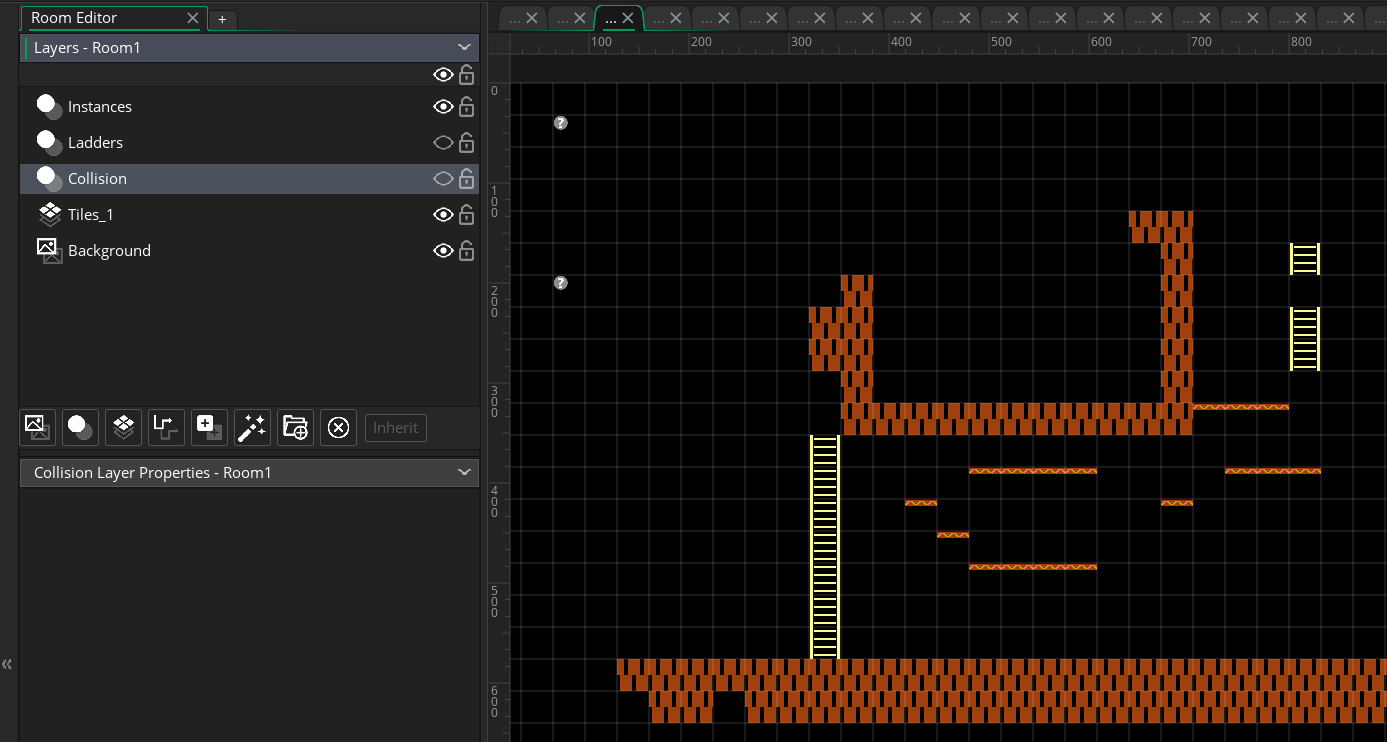

The tile editor works a bit like Photoshop, in that you can define different layers that are displayed on top of each other. The room tiles are usually the lowest layer, followed by a layer for “Collision” objects that define what you can and can’t bump into. You put collision objects on top of any part of the level that you don’t want the player to pass through. Then you set the Collision layer to be invisible. The top layer contains the objects themselves, including the player object.

Working with layers in the Room Editor

Movement

The player needs to be able to control this object, so I added some code to check if the left or right arrow keys had been pressed, and set a direction of motion variable if they were. Then for each frame of animation, called a “Step” in GameMaker, I added code to check the direction variable and update the position of the character. But before it moves the player, it first checks if that movement will collide with an object on the Collision layer.

What about vertical movement? When the player hits the jump button, I add a negative vertical movement speed variable. To simulate gravity, I slowly increase this variable in each step. I also check to see if this movement will collide with a collider object.

I wanted to include ladders, which are a special form of vertical movement. This required an additional invisible layer in the room, which I called “Ladders”. If the player “collides” with a ladder collider object, it changes the vertical movement speed to be steady in whatever direction the player chooses.

Enemies

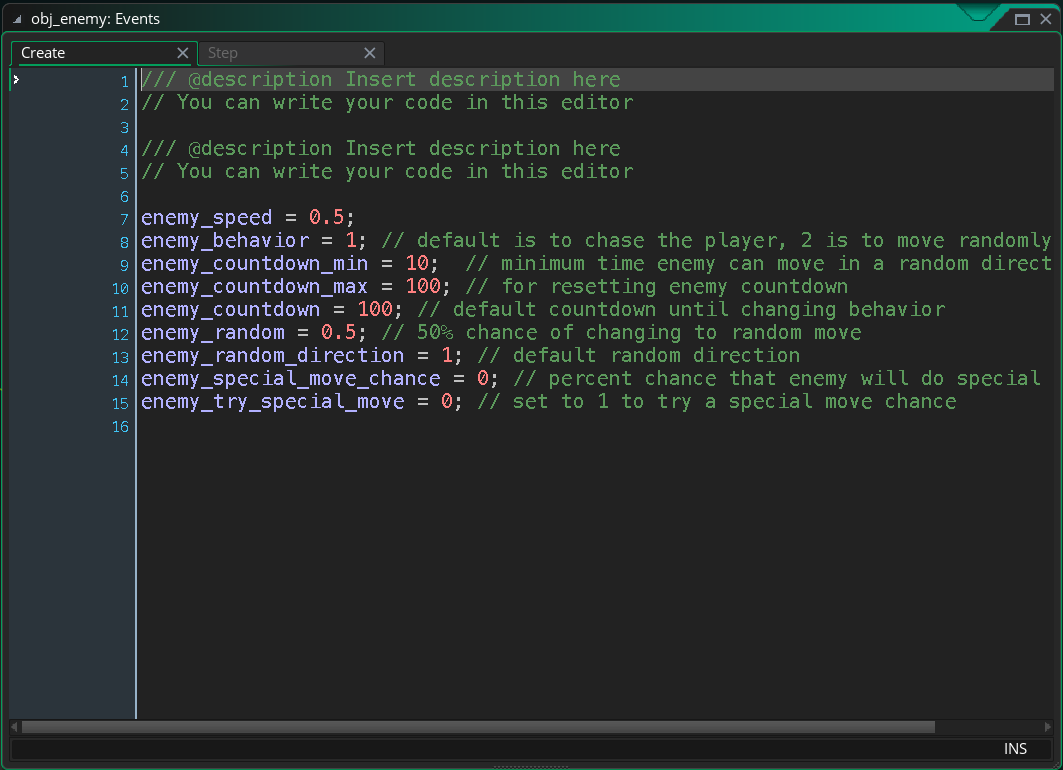

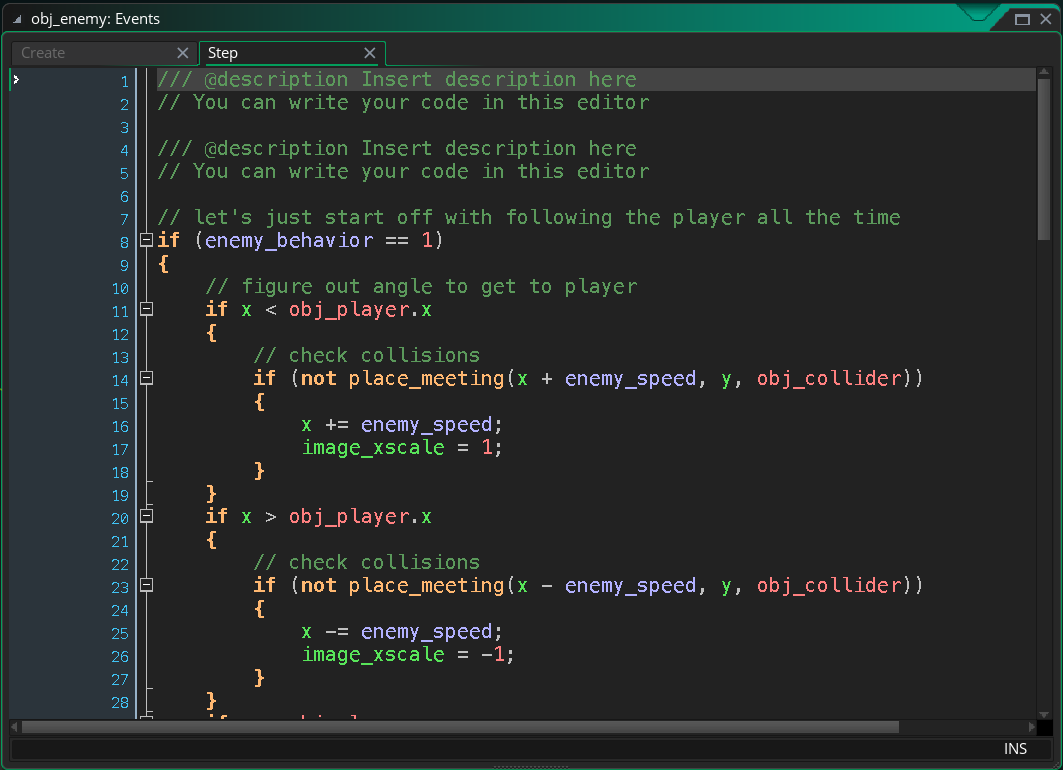

This was all well and good, but we need enemies to give the player a challenge. This is where the object-oriented nature of GameMaker’s coding language (GML for short) comes in handy. You can define a generalized “enemy” object, give it some default values for movement speed, and write the code that will make sure it too doesn’t run into walls. Then for each individual enemy, you create a new object that’s a “child” of the Enemy object. It will inherit all these default attributes, but you can add a sprite image and special code for any unique behaviors.

Setting the initial startup variables for the default enemy object

In the original game, I had some very simple code that took a random number between 0 and 1. If it was below 0.5, the enemy would move towards the player. If it was above 0.5, it would move in a random direction. This same strategy still worked in my modern game, although I had to add a timer variable so that the enemy would stick with one direction for a while and not just wiggle about.

The code for default enemy movement

I added a few other niceties, like coins for the player to collect, and ropes for the player to hang on. I also added the Key object, which when touched, advances the player to the next room.

Because the graphics were very simple, and the code was also simple, it didn’t take long to put all of this together. I didn’t keep a log of my time, but it was only a couple of weeks of work, a few hours at a time. And at this point, I had something that looked a lot like a complete game—it had a player-controlled character, it had platforming challenges, it had enemies and things to collect—surely finishing it would just be a matter of a bit of polishing, right? How long could that take?

Oh, you sweet summer child.

Stay tuned for Part 2!

Views: 5143

Facebook's Metaverse is already failing

Post #: 295

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2022-10-12 17:40:26.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: gaming metaverse

Sorry, Mark, nobody wants to join you here.

In a previous post called Why the Metaverse will never happen, I dissected the idea of the Metaverse as an impossible and ill-defined dream. Basically, the Metaverse has to be universal (like the Internet itself) or it isn’t a Metaverse at all, but just another Second Life clone. But tech companies will never agree to adopt a common framework that they don’t own and can’t fully monetize.

The other, more serious problem with a Metaverse is that nobody can actually define what it is. Mark Zuckerberg, in his ebullient announcement last year, said it would be a world “as detailed and convincing as this one” and that inside, “you’re going to be able to do almost anything you can imagine.”

This last sentence is a huge giveaway that Facebook’s Metaverse will fail. This is the same phrase spoken by dozens of naive and inexperienced wannabe game developers, who go on Kickstarter and announce an amazing new Massively Multiplayer Online (MMO) game where “you’ll be able to do anything.” Every single one of these Kickstarters, even the ones that reach their funding goals, end up failing spectacularly. The latest fiasco, DreamWorld, is a perfect example.

“Doing anything” is another way of saying “I have no idea what this game will be.” Games are fun because of constraints and rules. Take golf, for example. If you could just pick up the ball and drop it directly in the hole, nobody would bother playing it. But when you add the constraint of hitting the ball with a club, and add a scoring system, suddenly it’s interesting.

Not everything has to be a game, of course. Second Life, released in 2003, was the first successful attempt to make a virtual world that had no real objectives, other than building a world and exploring it with other people. But Second Life peaked in 2009 when it hit 88,000 concurrent online users. It’s still around, but these days nobody expects it to become the future of anything.

More recently, Minecraft was a much larger hit, capturing the imaginations of a huge portion of kids and teenagers. But Minecraft is definitely a game — it has very specific rules for breaking down blocks, finding resources, and using these resources to craft different types of blocks. There are even enemies to fight. It knows exactly what it wants to be and it does it very well. Countless Minecraft clones have been attempted, but they have all failed because “Minecraft, but better” isn’t a design document.

Getting back to Facebook’s Metaverse, it’s clear that Zuckerberg is serious about his effort. He’s spent $10 billion and hired 10,000 engineers. Surely, with this massive amount of resources, his company would have delivered something great, right? Right?

Well, as it turns out, what they’ve produced (which they call Horizon Worlds) is ill-defined, boring, buggy, and nobody wants to play it. According to leaked memos, the “aggregate weight of papercuts, stability issues, and bugs is making it too hard for our community to experience the magic of Horizon. Simply put, for an experience to become delightful and retentive, it must first be usable and well crafted.”

This is another giveaway that the folks building Horizon have no idea what they are actually trying to build. If a game is great, people will play it, even with crazy bugs. Skyrim shipped with tons of bugs, but the game was awesome from day one.

Horizon clearly isn't awesome. Second Life, and more recently, VR Chat, gained popularity because they offered a way for people to express unusual sexual desires in a safe place. But Mark Zuckerberg doesn't want any sex in his city. When people started harassing women in Horizon by trying to grope them between the legs, Facebook's answer wasn't to figure out how to deal with harassment. It was to permanently remove everybody's legs.

You can do anything you want. Except have legs, apparently.

Even Facebook employees don’t want to play Horizon. “For many of us, we don’t spend that much time in Horizon and our dogfooding dashboards show this pretty clearly,” another memo read. “Why is that? Why don’t we love the product we’ve built so much that we use it all the time? The simple truth is, if we don’t love it, how can we expect our users to love it?”

How indeed. The truth is simple: if the product was any good, people would play it. When Origin Systems was making the original Wing Commander, the entire company couldn’t stop playing the game. That’s how they knew it was going to be a hit. When Blizzard was building World of Warcraft, the company could barely get any work done because so many employees wanted to play it.

Facebook’s management, on the other hand, has decided that the way to fix their boring game is to force their employees to play it. “Everyone in this organization should make it their mission to fall in love with Horizon Worlds,” a recent memo read. “You can’t do that without using it. Get in there.”

The end result of all this will be a ton of wasted money and a product that may end up getting forced on people in order for senior management to report rosy numbers. But when the dust has settled, no amount of promotion and bundling will get people to keep playing something they don’t want to play.

UPDATE: Since this article was published, Facebook has triumphantly announced that Legs are coming soon. Are you excited? The message went over about as well as could be expected.

Views: 9483

The History of the ARM chip: Part 1

Post #: 294

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2022-09-26 22:09:45.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: articles

I'm excited to announce that Ars Technica has published the first part of my three-part series on the history of the ARM chip.

You can read it here: https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2022/09/a-history-of-arm-part-1-building-the-first-chip/

If you've ever wondered how your smartphone became so smart, it's because in 1983, a tiny computer company in England decided they would do something impossible.

I had a great time writing this article. I kept asking questions about CPUs, which I've always understood only at the highest levels. For example, I knew what RISC meant, it was "Reduced Instruction Set Computing". Okay, but HOW reduced? And what does an instruction set actually do?

Diving down the rabbit hole, I ended up learning how CPUs work from first principles. I've tried to share some of that knowledge in the article. I hope you enjoy it!

Views: 5443

So who am I?

I'm a writer and programmer. I write science fiction stories and novels.

I am the writer for the upcoming documentary series Arcade Dreams.

I also write technology articles for Ars Technica.

I'm the creator of newLISP on Rockets, a web development framework and blog application.

- Email: jeremy.reimer@gmail.com

Topics

3D Modeling

About Me

Amiga

Articles

Audio

Blockchain

Blog

Blogs

Book Reviews

Book review

Comics

Computer history

Computers

Computers Microhistory

Computing

Conventions

Crypto

Daily update

Entrepreneur

Family

Forum post

Gaming

Gaming Starcraft

Gaming metaverse

Internet

Jeremy Birthday

Keats

Kickstarter

Knotty Geeks

Knotty Geeks (video)

Market Share

Masters Trilogy

Monarch

Movies

My Non-Fiction

My Science Fiction

NewLISP Blog

Novels

OSY

Operating Systems

Pets

Poll

Reviews

Science Fiction

Servers

Software

Software Operating Systems

Space

Star Gamer

Star Trek

Starcraft

Television

Testing

Toys Childhood

Valheim

Wedding Marriage

Work

Work Life

World

Writing

RSS Feed for this blog

RSS Feed for this blog