Science fiction and technology writer

Popular blog posts

Recent forum posts

Discussion Forum

Discussion forumKnotty Geeks Episode 43 - Video Episode #1 - Microsoft Ruins Christmas

Post #: 243

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2020-02-26 21:41:58.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Knotty Geeks (video)

Happy New Year! Here's another exciting VIDEO episode of Knotty Geeks!

In this episode, we explore the INSIDE of a Starbucks, as we discuss Microsoft's peculiar position with Windows 10. Starting with a story of how Windows 10 ruined one woman's Christmas, we go back to look at why Microsoft made such drastic changes with Windows 8 in the first place, and how that affected the company's decisions going forward.

Views: 9737

Knotty Geeks Episode 42 - Video Episode #0

Post #: 242

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2015-12-22 10:33:28.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Knotty Geeks (video)

Yes, the vlogging we talked about in such wistful, hopeful terms in the last podcast has actually come to pass! It’s a Christmas miracle!

Join Terry and I in a very special Video Episode #0 of Knotty Geeks!

<iframe width="460" height="265" src=" https://www.youtube.com/embed/qgM-JPd8Mu4"; frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Show notes:

- Forever TV show

- Castles of Steel book

Views: 8587

Knotty Geeks Episode 41 - Vloggy Geeks

Post #: 241

Post type: Podcast

Date: 2015-11-12 11:26:51.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Knotty Geeks

Is Knotty Geeks going to video? We talk about way the show could become a vlog, how you can use Blender to edit video, and what the new YouTube Red service could mean for vlogs in general.

- Knotty Geeks going to vlogs?

- Starcraft II Legacy of the Void discussion

- Blender has video editing!

- YouTube launches YouTube Red subscriptions

- Google tailors web search results to your IP address

- New Compass card is kind of available

- New TV shows: Blind Sight, Mr. Robot, Quantico

Links:

* Blender Video Editing

* Blender Beginner Tutorial

* Simple Video Editing with Blender

* 4k vlogging camera

uploads/Knotty_Geeks_Episode_41.mp3" />

Knotty_Geeks_Episode_41.mp3" width="290" height="24" />

Direct link to podcast

Views: 8361

Knotty Geeks Episode 40 - The Beautiful Intelligence of Stephen Palmer

Post #: 240

Post type: Podcast

Date: 2015-10-21 10:16:18.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Knotty Geeks

We have a special treat on this episode of Knotty Geeks: an exclusive interview with British science-fiction writer Stephen Palmer, author of Beautiful Intelligence, an action-packed yet thought-provoking novel about the emergence of AI.

Terry and I talk to Stephen about how he got started in writing, how he views artificial intelligence and how it might develop, and we even get into the acceleration of technology and genetic engineering!

uploads/Knotty_Geeks_Episode_40-trimmed.mp3" />

Knotty_Geeks_Episode_40-trimmed.mp3" width="290" height="24" />

Direct link to podcast

Views: 8869

Knotty Geeks Episode 39 - The Berenstain Bears

Post #: 239

Post type: Podcast

Date: 2015-09-28 14:07:17.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Knotty Geeks

In this episode, we talk about an obscure book by Stanislaw Lem, the end of the Panorama Amiga Computer Club, and the possibility that the Berenstain Bears are proof of the existence of parallel universes.

Direct link to podcast

uploads/Knotty_Geeks_Episode_39.mp3" />

Knotty_Geeks_Episode_39.mp3" width="290" height="24" />

The Book No One Read: http://nautil.us/issue/17/big-bangs/the-book-no-one-read

Sci fi podcast Sword and Laser: "LEMming" http://swordandlaser.com

The end of the Panorama Amiga club: http://www.hk-soft.net/panorama/

Berenstain Bears parallel universe: http://www.avclub.com/article/how-you-spell-berenstain-bears-could-be-proof-para-223615

The Gods Must be Crazy old theatre: http://thetyee.ca/Entertainment/2005/04/04/ThisOldMovieHouse/

Google is Two Billion Lines of Code: http://www.wired.com/2015/09/google-2-billion-lines-codeand-one-place/

Did You Know YouTube videos: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YmwwrGV_aiE

Computers are breeding humans: http://duncantrussell.com/forum/discussion/14655/computers-are-starting-to-breed-humansno-really/p1

Erin McKean Kickstarter to add a million words to the dictionary: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1574790974/lets-add-a-million-missing-words-to-the-dictionary

Views: 8730

Knotty Geeks Episode 38 - Sad Puppies

Post #: 238

Post type: Podcast

Date: 2015-09-14 09:56:27.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Knotty Geeks

In this episode, we talk about the fallout from the recent Hugo Awards, and the ramifications of the Sad and Rabid Puppy campaigns. We also review one of the recent Hugo winners, the excellent novel "The Three Body Problem."

uploads/Knotty_Geeks_Episode_38.mp3" />

Knotty_Geeks_Episode_38.mp3" width="290" height="24" />

Direct link to podcast

Notes from the show:

http://www.wired.com/2015/08/won-science-fictions-hugo-awards-matters/

The Three Body Problem:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Three-Body-Problem-Cixin-Liu/dp/0765377063

Views: 9963

Knotty Geeks Episode 37 - The Creative Apocalypse

Post #: 237

Post type: Podcast

Date: 2015-09-07 12:58:03.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Knotty Geeks

In this episode, we review three great science fiction books, we talk about the upcoming improvements in Intel’s Skylake CPUs, and we discuss the strangely absent Cultural Apocalypse.

Notes from the show:

Beautiful Intelligence book:

http://www.amazon.ca/Beautiful-Intelligence-Stephen-Palmer-ebook/dp/B010NX6FV6

Gene Mapper book:

http://www.amazon.ca/Gene-Mapper-Taiyo-Fujii-ebook/dp/B00YG0K5M8

Gene inserting tool: CRISPR

Do we live in a simulation?

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/blogs/physics/2015/07/are-we-living-in-a-computer-simulation/

Reality Hack

http://www.amazon.ca/Reality-Hack-Niall-Teasdale-ebook/dp/B010VJECGC

Discussion of the Creative Apocalypse:

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/23/magazine/the-creative-apocalypse-that-wasnt.html

Background art:

http://www.angryboar.com/index.php/apocalypse-by-belgian-artist-jonas-de-ro/

uploads/Knotty_Geeks_Episode_37.mp3" />

Knotty_Geeks_Episode_37.mp3" width="290" height="24" />

Direct link to podcast

Views: 8435

Knotty Geeks Episode 36 - Knotty Geeks 2.0!

Post #: 236

Post type: Podcast

Date: 2015-08-10 09:42:44.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Knotty Geeks

In this episode, we reboot the entire podcast! Well, not really. We’ve come back to our favorite wedge-shaped Starbucks to rediscover what we really loved most about the podcast: the relentless acceleration of technology and the convergence of many technologies into fewer, more powerful ones. We talk a little bit about our writing project, the short story We Choose To Go, and discuss the future of human civilization. You know, just random stuff.

uploads/Knotty_Geeks_Episode_36.mp3" />

Knotty_Geeks_Episode_36.mp3" width="290" height="24" />

Direct link to podcast

Views: 7081

Zoe (1998-2015) The cat that nobody wanted

Post #: 235

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2015-06-08 13:41:42.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Pets

When I first met Zoe she was in bad shape. She was sitting in the back of a cage at the Vancouver SPCA. Her fur was matted and stringy, and she looked like the saddest creature I had ever seen. I put my fingers through the bars and she rubbed her chin on my hand. I fell instantly in love.

Zoe had been a stray as a young cat. She was rescued by the SPCA, then lived with a young family until her eighth birthday. At that point the family had a baby and bought another cat, and Zoe didn’t handle it well. Her card warned that she had issues with unwanted urination.

I watched as other people came into the shelter, petted Zoe, then read her card and walked on. Nobody wants middle-aged cats, and they certainly didn’t want one who had problems with peeing. I was going to pick her up right then, but I had to return the next day with proof that my building allowed pets. I vowed that if Zoe was still there when I got back that I would adopt her. Of course she was still available.

My friend Tzhe was with me and he drove us both home. I opened her cardboard box in the guest bathroom and she immediately jumped out and fled into the hidden depths of our walk-in closet. I had been a pet owner for thirty seconds now and already I felt like a failure. Fortunately Tzhe was able to coax her out and she slowly started to familiarize herself with her surroundings. She was incredibly nervous, but to my relief she did understand what to do when I repeatedly placed her on the litter box. Zoe had found her home.

A scared Zoe seconds after arriving at our home.

I bought a cat brush and groomed her twice a day, and her long hair became soft and lustrous again. She was initially very timid around strangers, but over the years she became more and more relaxed. She would hop up on the sofa as I played games or watched TV, and I would pet her for as long as she wanted. After a while she would hop down to the floor, flop over on her back, and I’d rub her tummy. Sometimes my wife and I would rub her face and ears at the same time and you could see her drinking in the affection like it was the sweetest wine. She never got tired of it. I could pet her until my hand felt like it was going to fall off and she would still want more.

Zoe after a few months, well-groomed and regal.

She was not a bold creature. One day I arrived home from work and she was meowing frantically next to a small bird that had gotten caught behind the blinds. She stood there as I rescued the poor frightened bird and guided it to freedom. Zoe loved to chase and eat flies, but anything larger was just too scary for her to deal with.

Zoe’s favorite game was “cat hockey”, where she would bat around a twist-tie and then leap after it. When we had our hardwood floors put in, we took Zoe with us to a nearby hotel while we literally waited for the dust to settle. After we returned, cat hockey was faster and more exciting.

Zoe expresses her love of the new floors

She wasn’t always easy to deal with. When I changed litter brands, she expressed her displeasure by peeing in my wife’s shoes. I switched back and all was well, but there was always the worry that she would urinate on things. When she got older I got a second litter box so she wouldn’t have to travel as far each time, but sometimes she still had accidents.

In her final years Zoe started to have health problems. Her kidneys and pancreas started acting up, and vet bills became expensive. But she never complained or got upset. She never lashed out at anyone. She was the sweetest creature I’d ever known, right up until the end.

A few days before she died, Zoe seemed to have a burst of energy. She desperately wanted to get into our bedroom, which we had always kept a cat-free zone because of my wife’s allergies. She had never before scratched at the door or tried to push her way in, and would even stop at the boundary if the door was open, knowing that she wasn’t allowed in. This time was different, however. She wanted to get in there one last time. My wife opened her eyes from a nap and saw Zoe sitting next to her, purring as if nothing was wrong.

I miss Zoe. She was my first pet, and I’ll never forget her. She was the cat that nobody wanted, but in the end I wanted her. And that made all the difference.

Views: 9247

Update on Furious, my visual novel

Post #: 234

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2015-04-02 09:41:00.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Writing, Gaming

Software developers are notorious for underestimating how much time their projects will take to complete. It’s not borne of ignorance or maliciousness, but rather optimism: one always thinks that everything will go as well as it possibly could. Reality has different ideas.

My initial estimate for completing my first visual novel was an optimistic six months. I’m now thoroughly stuck into development, and my revised estimate is about double that figure, although if I’m in line with estimates made anywhere else by anyone else ever, that figure will probably end up tripling.

Nevertheless, I’m really enjoying the development process. I started (as writers might) with the character outlines and then the script, but I found that keeping track of all the branching paths for the dialog in Scrivener was awkward and looked sort of like pseudocode. So I saved a step and moved into writing the game code itself, in a text editor, using the Ren’Py engine.

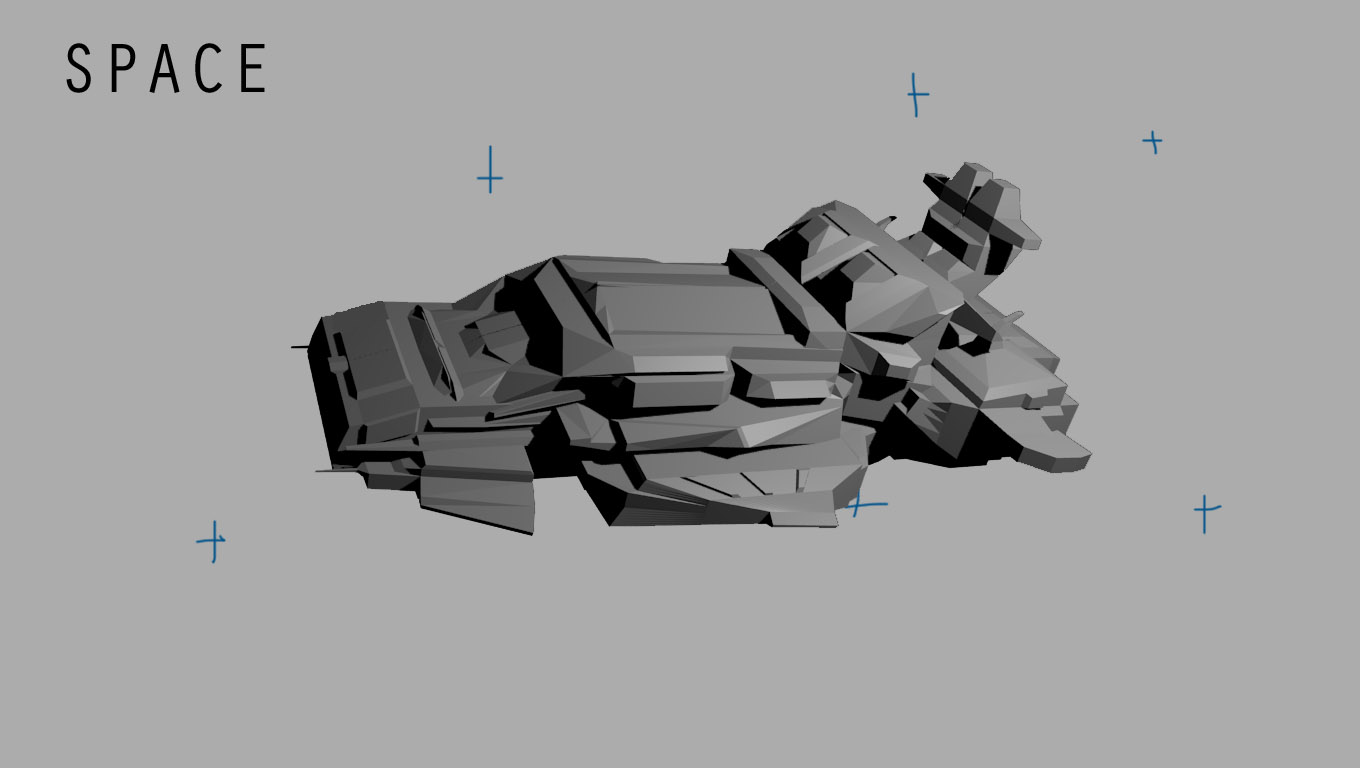

As I was essentially writing the game itself at that point, I needed art assets, and I was writing faster than I could create them. So I whipped up some really rough backgrounds and character sketches in Photoshop and used them as placeholders. They look terrible, but they get the job done. At the same time, I started in on some of the 3D assets using Blender, as you can see from this first look at the Furious space carrier, the seat of all the action in the game.

There are eight main characters (not including yourself and the Furious’ Captain) in the game, and six primary locations on the Furious. I’ve outlined the main arc of the plot, and it features eight flight missions with an “intermission” between each one where the player does most of the interaction with the characters. In theory, this should lead to a fairly simple game, but the number of interactions and branching paths can quickly get out of control.

To avoid getting into infinite branches, the primary plot elements are fixed. The main thing the player has control over are dialog options with the various pilots in between missions. Depending on what options the player chooses, pilots will gain or lose points in various internal characteristics, like affection (towards the player), confidence, or skill. These variables will affect the outcomes of future missions.

I’m trying not to make the dialog choices black and white, “you are great/you suck” options. My primary inspiration are the Telltale game series, like Game of Thrones, where you are often presented with two options that both seem bad in different ways. The hard part is making sure that these decisions affect the outcome of the game in a meaningful way. A recent game that does this really well is Dontnod’s Life is Strange, where the player can make significant changes to the plot by paying attention to small details in the environment and dialogue.

For me, writing this game is a huge learning experience, and I’m bound to make some mistakes along the way. Fortunately, my fears about doing a bad job are outweighed by the sheer fun of actually doing it. It’s just about the optimal balance for me of writing, storytelling, programming and artistic design. So stay tuned!

Views: 7382

So who am I?

I'm a writer and programmer. I write science fiction stories and novels.

I am the writer for the upcoming documentary series Arcade Dreams.

I also write technology articles for Ars Technica.

I'm the creator of newLISP on Rockets, a web development framework and blog application.

- Email: jeremy.reimer@gmail.com

Topics

3D Modeling

About Me

Amiga

Articles

Audio

Blockchain

Blog

Blogs

Book Reviews

Book review

Comics

Computer history

Computers

Computers Microhistory

Computing

Conventions

Crypto

Daily update

Entrepreneur

Family

Forum post

Gaming

Gaming Starcraft

Gaming metaverse

Internet

Jeremy Birthday

Keats

Kickstarter

Knotty Geeks

Knotty Geeks (video)

Market Share

Masters Trilogy

Monarch

Movies

My Non-Fiction

My Science Fiction

NewLISP Blog

Novels

OSY

Operating Systems

Pets

Poll

Reviews

Science Fiction

Servers

Software

Software Operating Systems

Space

Star Gamer

Star Trek

Starcraft

Television

Testing

Toys Childhood

Valheim

Wedding Marriage

Work

Work Life

World

Writing

RSS Feed for this blog

RSS Feed for this blog