Science fiction and technology writer

Popular blog posts

Recent forum posts

Discussion Forum

Discussion forumBuilding a virtual cottage and repairing my childhood

Post #: 315

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2025-10-17 22:19:25.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Valheim, gaming, Keats

In my post about my year in Valheim, I had one section that I always felt strangely bad about:

“At first I labelled many of my cottages in Valheim as Keats, but finally settled on just one that was on its own small island. But I didn’t end up spending a lot of time there. Hanging out in the virtual Keats didn’t feel like the real one. Some memories have to remain just memories.”

Why did that make me feel bad? To answer that, we have to travel back in time.

Many years ago, my great-grandmother Gladys MacLean (pictured above, center) and her husband bought a small parcel of land on Keats Island. On this beachfront property, my great-grandfather built a small white summer cottage. Because the property was mostly on a large outcropping of rock, he could build the cottage right on top of it, without a foundation.

This cottage became a precious memory for my mother, who remembered spending carefree days as a child exploring the beach and running up and down the island trails. And she was able to pass the cottage on to my sister and to myself, so it became a beloved part of my childhood as well. I remember scrambling down that enormous rock to explore the pebble-lined beach:

I remember the arbutus trees, the gorgeous smell of summer, and the day trips through the forest. I remember the silence, the taste of fresh huckleberries and blackberries, and the freedom to explore anywhere on the island that my feet could take me.

Here’s a picture of me, the little blonde kid, on the main deck at our Keats cottage. My sister is sitting on the large deck chair in front of me. Other relatives are hanging out around us. You can see the start of the fenced-off path in the upper-right of the frame.

The cottage was quite old by this time, and in dire need of repair. One room was starting to slope dangerously, and we were banished from one of the decks overlooking the beach. Some of the rooms, including one my mother had slept in as a child, were now inaccessible.

So my father drew up plans for a complete refit of the cottage. He even built multiple balsa wood models of the new house. For years we dreamed of what it might become. But the logistics and expense of bringing all the required materials to the island were too much to overcome. Then came the recession of 1982. My dad lost his job, and our family lost its financial stability. The plans to rebuild the cottage were put on hold indefinitely.

Money was tight. My mother got a job, saving us from utter poverty, but it wasn’t enough. So, reluctantly, she arranged for the sale of our Keats lot to our immediate neighbors, the multi-millionaire Bentall family. They gave us a good price. For them, it was a way to expand their property boundaries. For us, it was a way to survive.

They didn’t rebuild our cottage. Instead, they pushed it into the sea.

Looking through binoculars from across the narrow inlet, I could see the bare patch of rock staring back at me. It was an aching hole in my heart. For years I dreamed of buying a small patch of land on Keats Island and recreating, plank by plank, that dream that had been so cruelly taken from me. But as I slowly built up my savings, the price of land on that rocky isle increased beyond my means. It was never going to happen.

So, yeah, that’s why it hurt too much to build a new cottage on a virtual Keats in Valheim.

But lately, I’ve been trying to think of my childhood more as a beautiful gift that my parents gave me, and less of something that was taken from me before I was ready to let it go. My sun-dappled memories are still there, even if the cottage isn’t.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s enough.

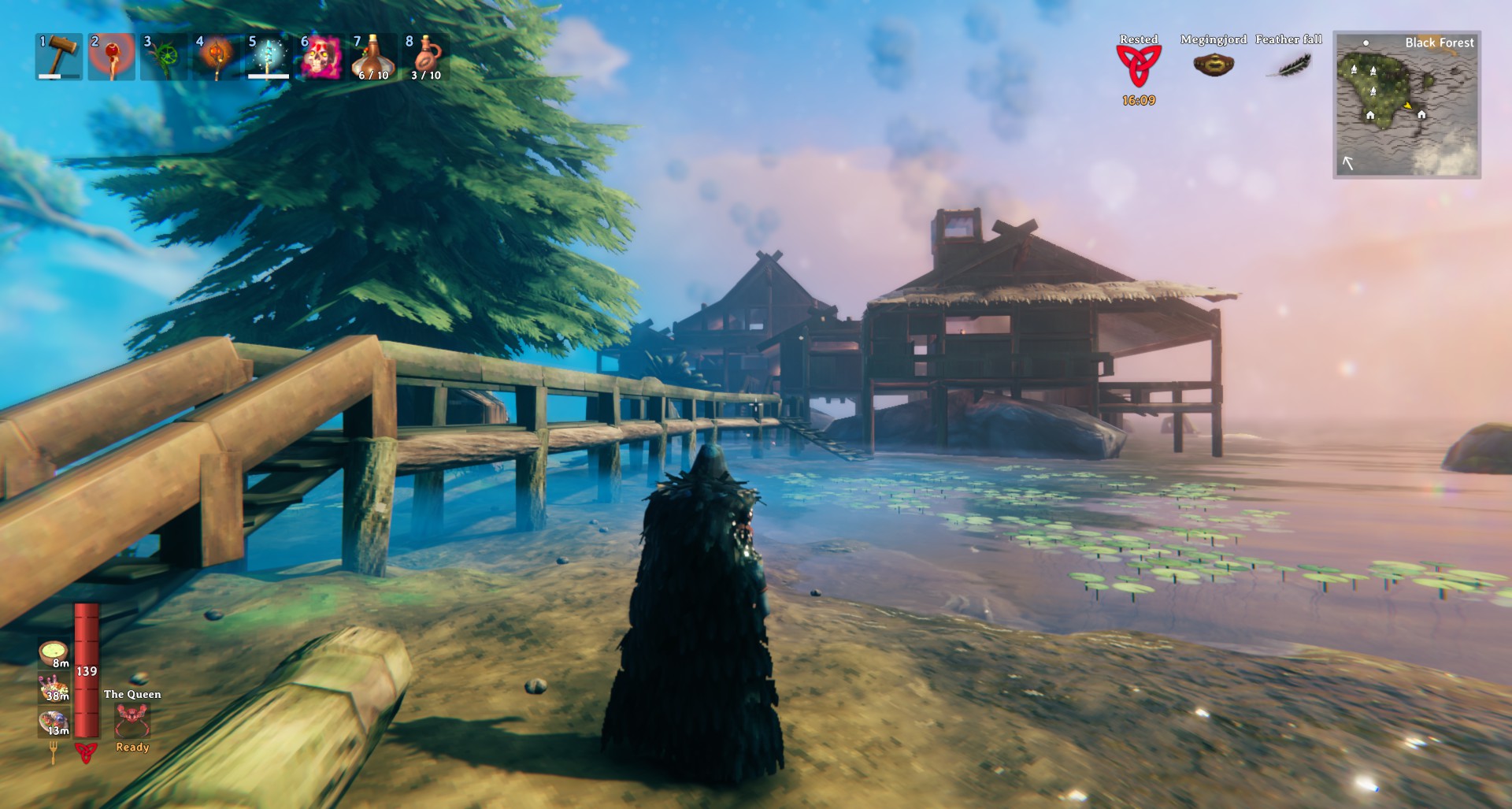

So, I decided to go back to the Valheim forest biome that I had dubbed Keats Island. The first step was finding the right location. And there it was, an outcropping of rock, perfect for building a dream cottage. The pine trees in the forest provided the logs to build the superstructure, perched on top of the rock just like our old cottage was.

I built a long, fenced-off walkway to the rest of the island. Our old cottage had a similar structure. It was meant to keep out the wandering deer. And luckily there were deer in the forest biome, but there were also a bunch of enemies like the greydwarves, trolls, and now bears, who would easily decimate the deer population given half a chance.

So I went and disposed of all these dreadful creatures, while sparing the deer. To prevent the monsters from respawning, I dropped campfires all over the island. I love that Valheim has this feature! Now it’s just me and the deer on Keats, just like it always was.

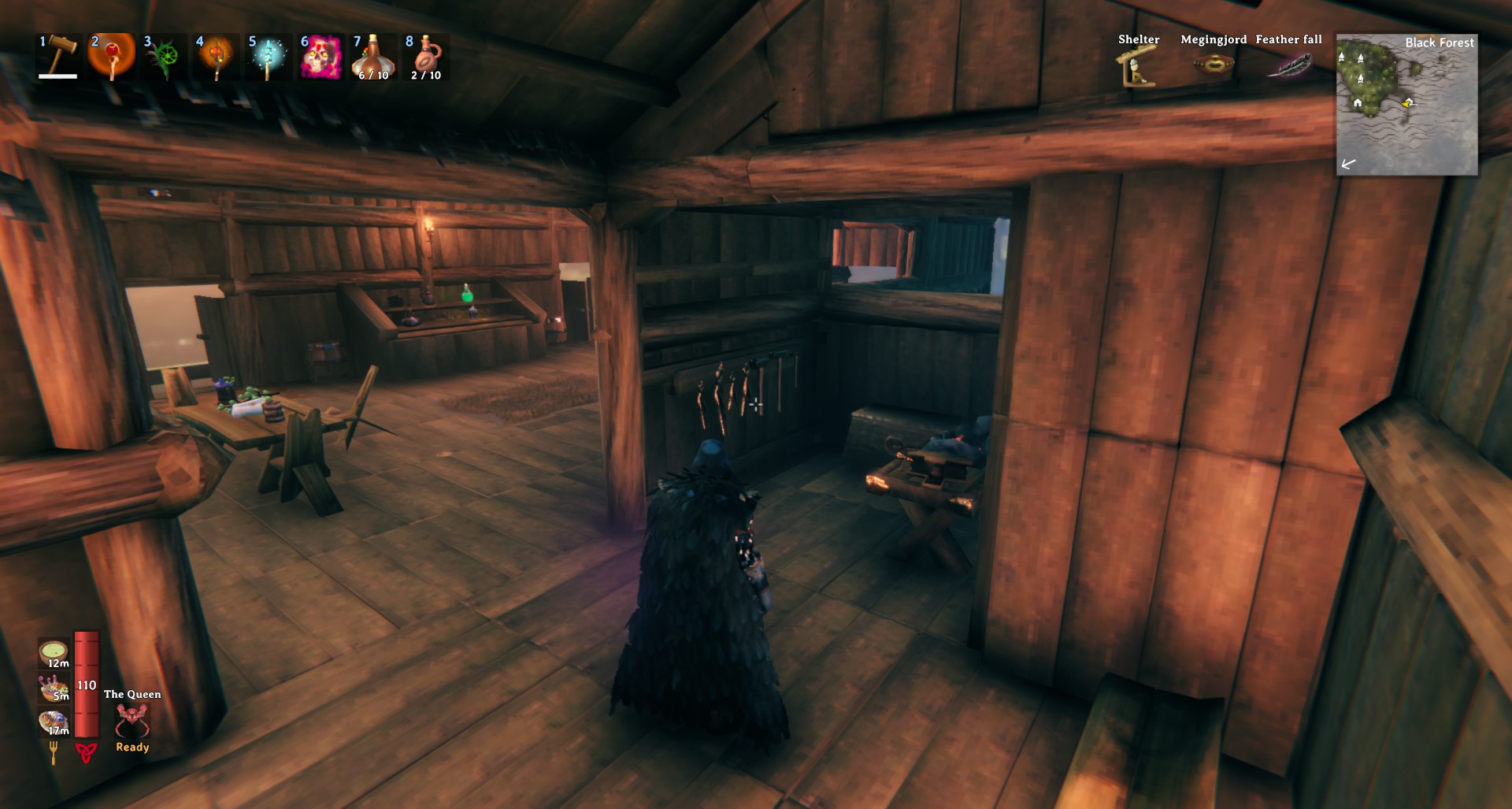

Near the front door hangs a sign, “MAXHOLME”. The same sign was on our Keats cottage. The “Max” part stood for MacLean, and the “Holme” was Home. My mother had held on to this sign until her death, but unfortunately it was lost afterwards. Now it lives again.

Entering in, you can see the tools hanging on the wall, always at the ready for any needed repairs.

The dining room is the centerpiece of the new cottage. The table provides a great view of the water.

I built a lovely little kitchen here, next to the dining room. It’s always ready for me to whip up a delicious meal for myself or for guests.

In the living room, the centerpiece is the roaring fireplace. Two of the dangerous bears that once roamed this island now face each other and ponder about what they did.

Upstairs, the master bedroom has a nice troll trophy and a great view of the island. The closets are full, ready for a guest to change into something more comfortable.

My great-grandmother had a lovely antique Singer sewing machine, so this room is home to the Valheim equivalent.

Finally, after a long day of relaxing on the island, it’s time to enjoy the sunset on the expansive deck.

So that’s my new beautiful Keats Cottage! I feel good about what I’ve built here. As I ease into an uncertain future, it’s nice to have something to feel proud of. Mostly, I’m happy to finally be at peace about my time on the real Keats Island. Now I can look at the small collection of beach pebbles and the tiny piece of wood I saved from the old cottage, and enjoy them as beautiful treasures.

Life will always be unpredictable. Sometimes we get thrown around between our triumphs and our tragedies like tiny dinghies on a rough ocean. But even after a loss, we can be thankful for the things we had, the people who meant so much to us, and for our happiest memories. These things can never be taken from us.

Views: 614

My History of the Internet (Part 3) is on Ars Technica!

Post #: 314

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2025-09-22 15:20:49.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: internet, computer history

The saga is complete! In this final installment, I discuss how the Internet changed post-dotcom collapse, explore how Google works and how it rose to power, and discuss the rise of social media and smartphones.

https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2025/09/a-history-of-the-internet-part-3-the-rise-of-the-user/

Views: 865

My History of the Internet (Part 2) is on Ars Technica!

Post #: 312

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2025-06-10 16:07:22.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: internet, computer history

The second part of my History of the Internet is up on Ars Technica! You can read it here:

https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2025/06/a-history-of-the-internet-part-2-the-high-tech-gold-rush-begins/

It was super fun writing this article. As I was firing up emulators for old computer hardware and operating systems and installing old browsers, it felt like I was getting pulled back in time. Back to the exciting and tumultuous 1990s! Come and join me!

Views: 1714

Micro History Episode 3 - Dan Meyer and the SWTP 6800

Post #: 311

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2025-06-09 18:06:17.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags:

This is a great story of a computer and an electronics pioneer who are almost totally unknown today. But Dan Meyer and the humble SWTP 6800 profoundly changed the entire landscape of the personal computing industry. They split the market into two parts: one who craved compatibility, clone hardware options, and the widest possible array of add-on hardware, and the other who valued innovation, simplicity, and elegant design.

No prizes for guessing which two camps these folks evolved into!

Views: 6491

My History of the Internet (Part 1) is on Ars Technica!

Post #: 310

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2025-04-21 15:44:50.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: internet, computer history

The first of my three-part article on the history of the Internet is up on Ars Technica!

It's getting some great reviews, including a video review from Vint Cerf, the father of the Internet and co-creator of TCP/IP. Which is really cool. Check it out:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/19htTKvmifeHH3mTj6fw5rmWAhA19O-bJ/view

Part 2 is on its way!

Views: 1724

I'm now (technically) a game developer

Post #: 309

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2025-03-07 20:31:52.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: gaming

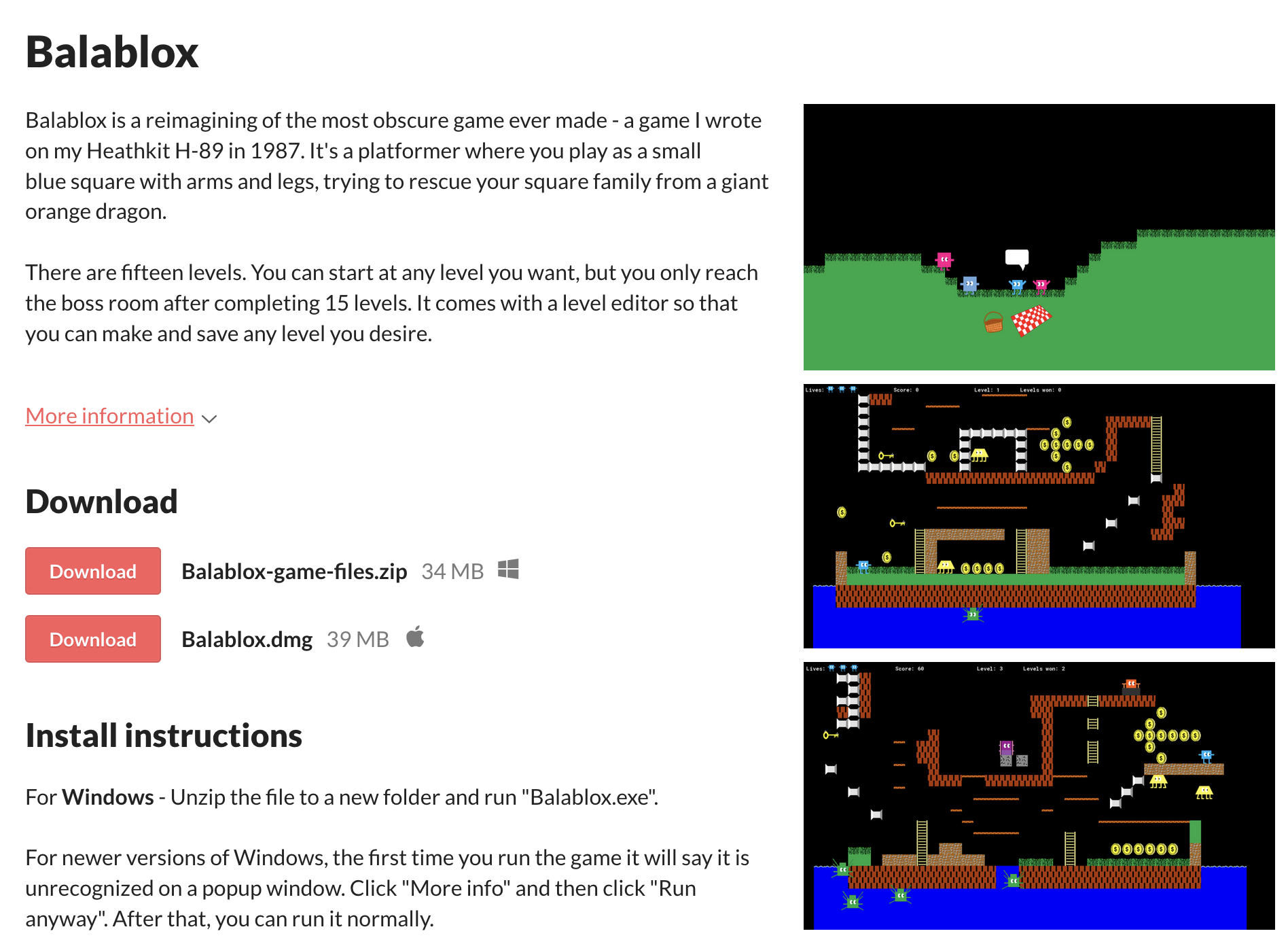

I was going to do a series of blog posts (you can read the first one here) about developing my "reimagined" Balablox, the most obscure game of all time. I also wanted to make it really polished and refined, with a full options screen with customizable controls and everything.

But years passed. And I was at a game developer conference and someone asked if I had published any games, and I had to explain this whole story to him.

He said: "Why don't you just put it on itch.io as it is?"

I was stunned. Of course! I could just do that. So I did.

It's really easy to publish on itch.io. It's less easy to get GameMaker Studio to actually generate an executable on macOS, but that's a rant for another day.

The game is free. It is provided as-is. I had fun with it. I hope someone else does too.

https://jeremyreimer.itch.io/balablox

Views: 2211

My year in Valheim

Post #: 308

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2025-01-25 21:36:39.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: gaming

Introduction

I never liked survival games. I preferred story-driven role-playing games, like the old Ultima series, Fallout, and Mass Effect.

But when Microsoft laid me off in January 2024, I found myself with a lot of time on my hands and no income. While I waited, perhaps in vain, for my industry to recover, I figured I should take a look at my gaming backlog. Surely there must be some titles in my Steam library that I could rediscover?

As far back as Ultima VI, I dreamed of a fantasy game where I could build my own castle. Why should Lord British get to look down his nose at us plebs from his massive fortress, when we’re the ones doing all the work to save the kingdom?

Just because you’re the king, that’s no reason to be so condescending

And so I came back to the world of Valheim, an indie survival game released in 2020, that had an emphasis on base building. Maybe this could work?

Little did I know how big this black hole of gaming was, and how close I was to the event horizon.

1. Meadows

Valheim starts you out in a vast world, alone, naked and afraid. You’re dropped to the ground by a giant raven during a thunderstorm. The bird, Hugin, at least gives you some starting tips before flying off again.

Like many survival crafting games, you start out by picking up rocks and sticks, and then you build a crude hammer. Now you can craft an axe and start chopping down trees. It’s a time-honored tradition by this point, but the Viking-themed world of Valheim is a little different. For one, it’s clearly not our world. A giant tree arcs through the blue skies, stretching from horizon to horizon, forever out of reach. And your journey starts in a group of giant stones, each one representing a boss monster that you have to defeat. This gives the game a set of objectives that are clear from the start. You could go fight the first boss right away if you wanted. But you’d probably die. You need to get stronger.

A vast world awaits…

While the meadows are peaceful in daytime, they get dangerous at night. Tree-like creatures called Greydwarves come out to menace you. The solution is to build an enclosed home out of wood, with a campfire to keep you warm, a roof to stop the rain, a door to keep out creatures, and a bed to sleep in.

This was about as far I had gotten in the game before I had given up, four years ago. Early on you get the sense that this is going to be a grind. You can make a crude bow to hunt frightened deer, then slowly collect enough leather to make better clothes. It takes a while.

I decided to abandon my old character, “Jeremy”, and begin anew on a fresh world with his twin, “EvilJeremy”. Of course, the twin had a goatee. I had only grown one once in real life, when I was feeling particularly disgruntled with the world. It seemed appropriate.

EvilJeremy was a bit more adventurous than his brother, and wanted to see what was beyond his initial shores. After constructing a makeshift home, I built a raft, sailed across an inlet, and landed on the far shore. I built a new house on a stretch of plain by the beach. On my map, I called this new place “Gibsons”.

In real life, I had been born in Vancouver and raised across the water in a small town that George Gibson had founded. For some reason, it felt reassuring to have my virtual avatar recreate the steps I had taken as a kid, so many years ago.

My new home in Gibsons

After upgrading my armor and my bow, I went to seek out the first boss, Eikthyr. He was a giant deer that shot bolts of electricity. Despite being scared, I managed to take him down and recovered pieces of his antlers. They were hard enough to break stone.

I felt like I was well on my way. I had no idea how naive I was.

2. Black Forest

The Black Forest is the first new biome you find in Valheim. It was a long way away from my home at Gibsons, more than a day’s walk in-game. So to make sure I had an easy escape route back home, I flattened the ground with my new hoe tool to make a primitive dirt road. I also built little shacks along the way that I could use to rest.

The dense forest is peppered with crypts, populated by nasty skeletons with swords and bows. These crypts taught me the ugly reality of death in Valheim. When I died in one, I revived back home in my Gibsons’ bed, but without any armor, weapons, or anything I had been carrying. I also lost points in every skill I had been training up until then.

You can go back to the site of your death — indicated by a skull and crossbones on your map and a glowing orb on the ground — and retrieve these items by wearing your backup armor, assuming you made some. But if you get killed again, you’ve lost both sets. To remind myself of the fragility of my life in Valheim, I crafted a third set of armor, and then left both the map icon and the orb undisturbed where I had fallen.

The forest is also home to giant blue Trolls, some of whom like to pick up entire trees and use the stripped logs as weapons. Unless you’re really good at dodging, one hit can kill you at this stage. But they can also help clear out the forest and even smash copper deposits for you in their misguided rage.

I’m not trollin, you’re Trollin!

The next boss, the Elder, wasn’t on this continent. I had to build a proper boat, sail off, and build a sort of forward base — which I named White Rock — on the coast of this new place. I made a nice little log cabin with a bed and a fire and everything. But when an army of Trolls with logs came to visit, they smashed not only me, not only my cabin, but also the bed I was sleeping in.

I died and was resurrected at the starting stones. Getting back required building a new boat. Sailing at night is scary. You can’t see much, especially if there are clouds, and sometimes giant serpents will chase you.

When I finally made it to the Elder, I was unprepared for the fight. The giant tree shot out tangled branches that collided with my face, and raised evil roots that tore at my feet. Weighed down by my bronze armor, it was hard to dash in and recover the items from my corpse.

Eventually I figured out the pattern and downed the boss. I was awarded a Swamp Key. Great, but why would I want to go into the swamps?

3. Swamp

The whole purpose of my playing was to build a castle, right? But up until now I could only build wooden structures. Building stone walls required a stonecutter, and that required iron. And iron was inconveniently buried deep in the swamplands, inside sunken dungeons.

Apparently an ancient humanoid race, the Draugr, had mined all the iron and built a great civilization, before making a key strategic mistake: going to war with the gods of Aesir and Vanir. They lost badly and the gods buried their settlements and them. They ended up walking their forsaken land as undead warriors, fighting their final hopeless battle forever.

The swamps are dark, damp, and dangerous.

Draugr are horrifying and deadly. I found a swamp on a nearby continent and built a new base, Nanaimo, in a forest next to the Draugr. I tried to be extremely careful, cutting down trees, building torches, and flattening the land with my hoe so that I wouldn’t constantly fall into deep puddles and get killed by leeches. It took forever to tame the swamp, but I kept going.

I was unlucky and the strip of swamp I had found contained only one dungeon. And that dungeon contained many nightmare bone piles that constantly spawned new Draugr, including elites. I died a few times. But I persevered, and got enough iron to at least build a small castle in Nanaimo.

My first castle. I even dug a moat!

So I’d achieved my initial goal, right? I could stop playing? In theory, yes. But it didn’t feel right. Not yet. There was a giant swamp monster, Bonemass, to defeat. I was scared of his massive blobby arms and his poison attacks, so I built a little house on top of a giant tree and peppered him from afar with frost arrows.

My prize was a mystical wishbone, which apparently could find treasures and silver deposits. My quest wasn’t over just yet. It was time to head up into the mountains.

4. Mountains

Like Mordor, you can’t simply walk into the mountains. It’s cold, and you’ll freeze to death, unless you prepared some frost potions ahead of time. Even if your blood is full of antifreeze, there are packs of wolves that would really like to have you for breakfast.

I enjoyed my time in the mountains. There were abandoned castles everywhere waiting for me to claim them and restore them. Searching for buried silver veins was fun and rewarding. When packs of wolves attacked, I sometimes had to escape by sliding down the snowy slopes. I built base camps and equipped them with carts to haul the silver ore back to Gibsons, ready to smelt into shiny new armor.

Castles… castles everywhere…

Flying drakes guarded dragon eggs, and once I had liberated three of them I could summon the next boss, Moder. I prepared a lot for this encounter. I cleared out and flattened the area surrounding Moder’s temple, and even walled it off so that nosy wolves and ice beasts couldn’t interrupt me in the middle of battle. I used my hoe to raise the ground into giant columns of stone that I could use to hide behind when Moder attacked with her frozen breath.

It felt good to be over-prepared. Moder fell to my onslaught and I was rewarded with a set of dragon tears. These apparently were necessary to build a whole bunch of new stuff, like Artisan Tables, which let me build even more new stuff, like windmills, spinning wheels, and stone ovens.

I felt like a kid getting a whole bunch of new LEGO sets to play with. And I realized that it was time to take my toys and start building a place that I could really be proud of.

Intermission - Founding a city

I sailed back across the inlet and saw my first home, still standing where I had left it. This would be the site, I decided. I named the place Vancouver, the same as my real-life birthplace, and the city I came back to for high school and university. In the game and in reality, Vancouver was a place I would often travel away from, but would always come back to. It was, and is, my home.

Valheim has an optional multi-player cooperative mode, so in theory I could have invited my friends over to help me build this settlement. But my friends had either stopped playing Valheim or didn’t want to start. I would have to engage in this massive building effort by myself.

It took a lot of stone and iron to make this place. I found a site, way off on another continent, that was full of boulders. I constructed a portal to get there and back quickly. Iron ore couldn’t be transported through portals, so I had to build a longship to take me far away to new and even more distant swamps.

Building the castle. My first house is in the background.

Sailing off to get more iron was surprisingly relaxing, especially now that I had the speed, armor, and weapons to either avoid or fight serpents. Finding the wind, charting a course — it reminded me of happier days in childhood, when my sister and I would take out the little dingy and sail around Keats Island.

At first I labelled many of my cottages in Valheim as Keats, but finally settled on just one that was on its own small island. But I didn’t end up spending a lot of time there. Hanging out in the virtual Keats didn’t feel like the real one. Some memories have to remain just memories.

Constructing the Great Hall

To make sea voyages shorter, I took my pickaxe and carved out a small canal through an isthmus that was preventing me from sailing west. I can’t think of many games that would allow you to do that, let alone preserve every road I paved, every rock I carved, and even every object I dropped over an entire world. This made Valheim seem more like a place that I really inhabited, a world that I could make massive changes to over time.

Vancouver comes to life

The castle and city I built in Vancouver was evidence of that. It started with just a single tower. Eventually I built stone roads connecting outlying settlements, made streets and avenues and parks and houses and farms, and even a Great Hall to celebrate all my accomplishments. I even tamed a pair of wolves and filled my stone hallways with their happy doggy offspring.

Happy puppers

In the real world, I will never be able to afford a house in the city. But Valheim has no such limitations. I could make as many houses as I wanted.

But still, across the sea, the wind-swept plains beckoned. There was more to do out there. I didn’t want to stop just yet.

5. Plains

The plains used to mean death. Literally. Giant “Deathsquitos” would swoop out of the sky and kill me in one bite. It wasn’t a pleasant place to be at first, but as my armor and health improved, it became a second home.

I shared that home with the giant Lox, sort of a cross between bison and lizards. They scared easily and were tough to fight, but after trapping one in a pit I dug out of the ground, he calmed down and allowed me to tame him. I kept “Snuffy” at my base, where I fed him cloudberries and petted him and told him he was a good boy.

He saved my life more than once. One time, a giant flying bug from the neighboring Mistlands followed me home and swooped down upon me. Snuffy woke up and saved the day, as well as my base.

It was a sad day when Snuffy died. I was outside at night, surrounded by Fulings, short, goblin-like creatures with spears and torches. He burst out of his pen and broke through my stone walls just to tear through the green monsters. He saved me, but gave his life to a Deathsquito. I never tamed a Lox again.

RIP Snuffy

The plains were filled with Fuling camps. Taking them down was tricky. Not only would the smaller goblins swarm me, but the giant Berserkers would smash my face in while their magic users rained down fiery death. It took all of my skills, a ton of rest, and the best healthy foods to even attempt to take them over. But when I did, the camps were now mine. I had built my main base in the plains on top of one of the former camps. It felt good. I was taking back this world from my many enemies, one town at a time.

The Fuling camps also contained mysterious totems, which I discovered were the key to summoning their god, the horrid creature Yagluth. I landed on the swamps of another continent with my bow already singing, like it was the beaches of Normandy. I slowly built bases closer and closer to Yagluth’s temple. Finally, I summoned the demon.

This monster hurled fire and doom at me endlessly. I had tried to prepare, building tunnels down underneath the temple where I could rest and repair. But I still died, over and over again. Fortunately, I had multiple sets of backup armor, and a portal that got me right back into the fight. Yagluth eventually went down, but I was exhausted. Was this game really worth this kind of stress?

Little did I know that my stress was only beginning.

6. Mistlands

It’s a beautiful place, if only you could see it.

The Mistlands are aptly named. A thick grey mist pervades almost all of it, and while you can take out a Wisp to light up your immediate surroundings, you’re basically stumbling around blind.

It’s also a horrible place, full of giant bugs called Seekers that fly out of the mist to kill you when you’re least prepared. It’s full of crazy peaks and valleys that make it easy to get stuck. And when you get stuck, that’s when you hear the foghorn that signals your doom.

I ventured cautiously at first into the Mistlands from my base in the adjacent plains. I met the Dvergr, a group of mining dwarves who were the first friendly folks I’d met in Valheim. They had a bunch of bases deep inside the mist. They were ferrying some mysterious cargo and warned me about the Gjall.

They ought to have heeded their own warnings.

These floating gasbags signaled their arrival first with a blast from their horns, then with rivers of fire and oceans of blood-sucking giant ticks. Many of the Dvergr bases I found would end up gutted by these terrors, leaving no survivors. And I too got caught by them, leaving two corpses in a literal Death Valley for future archaeologists to wonder about.

A destroyed Dvergr base

In order to make the armor you need to survive, you have to venture into the worst part of the Mistlands: the infested mines. These are literally crawling with horrid bugs, ticks, and other creepy things. There are twists and turns and holes in the floor you can fall through. It’s not easy to get out alive, let alone with the precious Black Cores you need.

The worst part about the Mistlands was finding out that I was in the wrong Mistlands — my lovely base in the Plains bordered the largest chunk of the misty place I could find, but it was the wrong chunk. The Queen was holed up on the coast of an entirely different continent.

I thought maybe I could try an amphibious assault. I was wrong. Gjalls patrolled the Queen’s lair and blasted me off the tiny island I was using as a foothold, just so the giant ticks could surround me and bleed me to death.

I realized I had to take a slow and steady approach. I made landfall far away from the Queen on an adjacent continent, and pushed my way though to the spot where it was close to the Mistlands. But I needed to somehow bridge the gap between the jagged coast and a safe spot for an inland base.

I built a long and winding wooden bridge around the coast and up the mountains. When Gjalls showed up, I’d run away and snipe them with my crossbow. Eventually I found an abandoned Dvergr tower looking over a flat area surrounded by mountains. A perfect place for my Mistlands base.

My little home in the misty hells

From this base, I slowly moved forward towards the Queen. I’d extend my stone path and walls until I reached a safe spot where I’d build another portal. These forward bases allowed me to retreat when things got dicey. I also constructed many wisplights, their pale blue glow pushing away the mist in the surrounding area, making the path visible at last.

It was slow going, but it felt like I was taming the Mistlands. Eventually I reached the Queen’s lair, and cleared out its guardians. I felt like I was ready. I felt prepared.

I was wrong.

7. The Queen

The Queen was a horrible nightmare of a beast, a giant crawling bug with razor-sharp pincers and a hairy tail. Even when I perfectly parried her attacks, she would push me back across the dungeon, which was — of course! — shrouded in mist. Then she’d summon more flying Seeker bugs to attack me, and spew up a firehose of poison and tiny bugs. If she got bored, she’d burrow in the ground and reappear somewhere high up, out of reach and out of sight.

I could get her health down a little, but she would wear me down, drain me of all my health potions, and chase me out of her lair. It felt exhausting to fight her.

And why was I fighting her in the first place? She was sealed up in her lair, not bothering anyone outside in the world. All I had wanted from this game was my castle, and I had that. Why not just give up?

I couldn’t give up. I had one last black can of cherry cider in my fridge, and I decided that I would drink that cider when I killed the Queen.

I scoured the Internet for hints and tricks. Everyone agreed that attacking her with a sword and shield was a bad idea. The answer was to use magic. But training in magic required crafting a whole new set of cloth armor and cooking up entirely new foods. It meant going back into the infested mines to grab more Black Cores, and scouring the Mistlands for black skulls filled with soft tissue that I could refine into magic Eitr. It meant slowly leveling up skills that I’d never used before.

I did all that. I raised my new Elemental staff above my head and cast my protective shield bubble. Then I went in to face the Queen as a powerful fire mage.

A few minutes into the fight, a seeker bug popped my bubble and propelled me across the floor, straight into the Queen, who killed me with one hit.

I gave up for a while after that.

Every time I opened the fridge, that last can of cider would stare back at me, mocking me for my failure. I wondered what I was doing. Why was I spending so much time and so much emotional energy on a computer game? Why did it matter so much to me?

I didn’t have answers for those questions, at least none that I wanted to dive into too deeply.

But I decided I would make a plan. I would train. Like Rocky Balboa, except with fireballs instead of fists.

I found a spot in the swamp with a pair of bone piles, spawning endless Draugr. Once, I would have run from such a place. Now, it was to be my salvation.

I would portal in, blast undead warriors for an entire in-game day, then return home to rest and recuperate.

My Elemental magic slowly went up. I could cast more spells without being drained. Even my shield bubble got slightly stronger.

It was time.

I returned to the Queen, and poured fire into her oozing carapace. Over and over again. She would attack, and I would run.

I killed her.

That cider was the most delicious drink I ever had.

The Queen is dead, long live the Queen

Conclusions

I have spent over 700 hours playing Valheim. It’s a number that’s easy to criticize, or to mock.

But those hours have been mostly happy ones.

I have built castles and founded cities. I have cleared forests, drained swamps, and criss-crossed continents with roads. I have dug canals and sailed through them with mighty ships. I have climbed mountains and defeated dragons.

All in all, I’ve had a good time.

But it feels more than that, somehow. It’s all the little memories that happened along the way, memories that are only mine. It’s that time I taunted a troll from my boat by shooting him with fire arrows, and watched in horror as he waded through the water to smash me to pieces. It’s the time I wandered through the forest and recovered two lost tamed wolves, only to have one die to a marauding skeleton and the other give birth to his successor.

It’s all these memories, and also just moments of watching the sun go down over the water. Or watching the sky clear up after a thunderstorm.

Real life is like this as well. We have our triumphs, and our tragedies. But sometimes the moments that mean the most to us are the small ones. Times we spent with people we love. Times we spent alone.

In the end, isn’t it enough that we were here? That we lived in this world?

I’m looking for work again. It’s a slow and frustrating process. Sometimes it seems like everything is getting harder. I’m definitely getting older. For the first time, I’m realizing that there are more years behind me than there are ahead.

But I’m still here. And I’m still dreaming of a world I can help build.

Sunset in Valheim

Comments (1)

Views: 4889

Micro History Episode 2 is up!

Post #: 305

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2024-07-19 21:00:55.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags:

This one's a doozy - welcome to the crazy world of personal computers in the 1970s. This story has it all - bad managers, overworked engineers, mandatory "training" based on crazy cult-like seminars... and it ends with the most bizarre implosion in the history of tax evasion.

Plus, some computer history! The IMSAI was the world's first personal computer clone, a 100% compatible copy of the MITS Altair 8800. It set the stage for other companies to clone the IBM PC later on, which changed the world forever.

Plus plus plus, the first appearance of Gary Kildall and CP/M! But definitely not the last.

Enjoy!

Views: 2886

My article on the history of public messaging is up on Ars Technica!

Post #: 304

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2024-04-29 15:02:37.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags: Articles

This article was deeply personal to me, because my life overlapped with so much of it.

It starts out with the earliest networked computers (PLATO, and the Arpanet) and goes through BBSes, Usenet, web-based forums, and social media. It's a wild ride.

Check it out!

https://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2024/04/first-post-a-history-of-online-public-messaging

Views: 3643

Micro History Episode 0 is up!

Post #: 303

Post type: Blog post

Date: 2024-04-23 17:38:49.000

Author: Jeremy Reimer

Tags:

It's an exciting beginning for me, the culmination of a dream I've had for a long time, to chronicle the entire history of personal computing.

Enjoy and don't forget to like the video and subscribe to the channel!

Views: 10242

So who am I?

I'm a writer and programmer. I write science fiction stories and novels.

I am the writer for the upcoming documentary series Arcade Dreams.

I also write technology articles for Ars Technica.

I'm the creator of newLISP on Rockets, a web development framework and blog application.

- Email: jeremy.reimer@gmail.com

Topics

3D Modeling

About Me

Amiga

Articles

Audio

Blockchain

Blog

Blogs

Book Reviews

Book review

Comics

Computer history

Computers

Computers Microhistory

Computing

Conventions

Crypto

Daily update

Entrepreneur

Family

Forum post

Gaming

Gaming Starcraft

Gaming metaverse

Internet

Jeremy Birthday

Keats

Kickstarter

Knotty Geeks

Knotty Geeks (video)

Market Share

Masters Trilogy

Monarch

Movies

My Non-Fiction

My Science Fiction

NewLISP Blog

Novels

OSY

Operating Systems

Pets

Poll

Reviews

Science Fiction

Servers

Software

Software Operating Systems

Space

Star Gamer

Star Trek

Starcraft

Television

Testing

Toys Childhood

Valheim

Wedding Marriage

Work

Work Life

World

Writing

RSS Feed for this blog

RSS Feed for this blog